| This poster was produced by the Canadian government in 1907. Perhaps John saw one like it. During the early years of the 20th century, Canada had agents in many western border states, promoting immigration. These agents were paid a commission for each person they persuaded to settle in western Canada. | Image credit: National Archives of Canada |

Finally, Land!

John's desire to own land remained strong:

We had not been out west long before interest built up in free land available to homesteaders in Alberta, Canada. This was of interest to Dad because he wanted some land, so off to Alberta we went.

And so they did. Once again, John loaded their belongings, farm equipment, and horses, along with Minnie and the children, onto an immigrant train—this time, bound for Alberta, Canada. Minnie was about six months pregnant. The children were ages eight, five, four and two and a half. As if this were not enough of a burden for Minnie, Anna contracted whooping cough:

We traveled to Alberta on an immigrant train, which had both freight and passenger cars on it. The most persistent and worrisome thing even to me, a little over 5 years old, was my sister Anna, who had a serious case of whooping cough. The whooping and gagging made me fear that she would die. I am sure the concern that showed on our tired mother's face had some bearing on causing that fear even though she never verbally expressed it that I remember. The whooping cough caused pneumonia to develop after a short time. She was a very sick and weak child. It still seems a miracle that she survived.

Meanwhile…

which was a freight car where one could load all manner of possessions an immigrant might own and want to transport to his new location, which in our case included machinery, horses, furniture and any other possessions there was room to pack in. The horses were barricaded away from the rest of the freight near the center of the freight car where one door was left open for ventilation and light and also barricaded so horses could not escape. One unusual thing was a 10 gallon cream can nearly full of breadcrumbs. The reason for the can of breadcrumbs was that our mother made a very hard crusted bread and as I remember it all of us children liked to eat that bread (I still like hard crusted bread after 80 years). When that kind of bread is sliced, it makes a lot of coarse crumbs. Mom saved them to use for chicken feed when we arrived at our new homestead. For some reason this can was near the door, perhaps as a seat.

a commotion among the horses arose and one of them knocked the can of crumbs out of the freight car door below the barricade. It bounded down the mountainside and after the first bound or two the lid came off, scattering bread crumbs far and wide. I imagine birds, mice and other creatures had a grand and exciting picnic in that area of the wild.

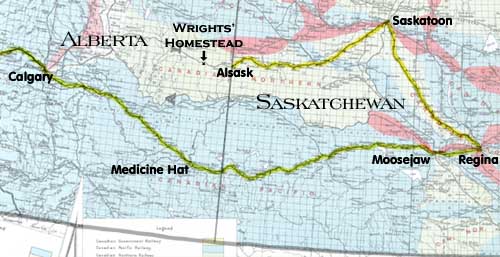

| The last part of the likely route taken by the Wrights' immigrant train is highlighted on this detail from the pages of a 1915 Canada Atlas. (To view a larger scale image showing the entire route, click the map. But be warned that this is a 500KB download.) This reconstructed route is based primarily on Irvine's memoirs. The location of the Wrights' homestead is indicated above and left of center. To judge distance, note that each small square on the map is a township, approximately six miles on a side.

The highlighted line running from Saskatoon (upper right) to Alsask is the Canadian Northern Railroad's Goose Lake Line. Eventually it would run all the way to Calgary (far left), passing very close to the Wrights' homestead. But in 1911, it was completed only as far as Alsask, on the Alberta/Saskatchewan border.

This route would have involved many switches between railroads and rail lines, each with a significant layover, no doubt, just as Lloyd describes. But there does not seem to be any record of just how long the trip actually took. |

Generally, the immigrant train moved quite slowly and also had quite a little layover time. At times, it got very boring to me. I remember one time we were put off the train for quite a while for the train crew to do some switching. It seems we were supposed to be back at the depot at a certain time but we had to wait for what seemed [to me] like an interminably long time—not too surprising, since I was five years old and tighter than a fiddle string. I was getting very fidgety. Finally the engine was pulling slowly into the station and I became uncontrollably excited and dashed across the track amid screams of, “Come back! Come back!” So I came back, this time amid screams of, “Stay there! Stay there!” That steam engine looked awfully big just a few feet away as I returned. If I had fallen I wouldn't have had time to get out of the way nor would the engine have had time to stop. It is almost as much of a miracle that my folks survived that trip as that I did.

But surviving the trip was only the beginning. Lloyd doesn't mention it, but there would have been a thirty mile journey across country after they got themselves and their possessions off the train at Alsask. And it seems as though it would have taken several trips to get all their belongings and all the farm equipment to the homestead. In another year or two, the Canadian Northern Railroad's Goose Lake Line would run within three miles of the Wrights' homestead. But the Alberta portion of that line was just being surveyed. It would be over a year before the rails were laid, and more before trains were running regularly.

We finally arrived at our future home site on May 2, 1911. I was a little over five years old. The first thing was establishing a home. Dad had brought a large tent and put it up and that would be our home for most of the summer while a sod house was being built.

This must have seemed like an extended camping trip for the children. But what a burden it must have been for Minnie to set up housekeeping in a tent, in an unfamiliar place, with four young children, while in the third trimester of pregnancy! They were still living in the tent on July 22 when child number five, Earl Hawkins, was born.

A five-year-old boy's mind was on other things, though. There was a sod house a-building, and Lloyd's detailed recollection betrays a fascination with the process.

Near the site where the house was to be built was a low area where water would stand a short time after the snow melted off. This area produced a very coarse grass that would get 20 to 30 inches tall depending on the depth of the water. It had very coarse roots, which would make a good sod to build with. The sod house was built with a sod that was plowed from this area. All the old grass and the new which had already started to grow through it was mowed and raked off. This sod was plowed with a 16-inch plow called a sod plow. The sections of sod were cut about 32 inches long. The ground the sod was cut from was plowed about 4 inches deep. This gave us

These pieces were laid similar to bricks [two alternating courses deep, giving] us a sod wall about two feet thick. The wall was built about 8 feet high and the dimensions of the structure were 18 feet by 36 feet. Before the wall was completed, large pieces of two inch planks were built into it. The planks had large bolts in them about three feet long, to fasten the roof down with. (This precaution was not taken by a neighbor of ours and their roof blew off in a big wind storm which was very common on the prairie.) The roof had almost no eaves as further precaution against wind.

The roof was made of shiplap laid over 2 by 6 or 2 by 8 inch [rafters, and] covered with a single layer of a material called

Over this was a single layer of sod to protect the Ruberoid from the sun and to make the house warmer and also to weight the roof so the wind would not blow it off. As yet further wind protection, an extra layer of sod was placed all around the edge of the roof. A neighbor didn't put an extra weight on his and

| This sod house in South Dakota seems to illustrate the rounded roof construction Lloyd describes. |

I do not remember how much of an arch there was in the roof but I would guess that it was three feet higher in the center than at the top of the side walls. It was a completely rounded roof 36 feet long. Looking at the east and west ends it was like this:

The north side was like this:

and south the same except for a door in the middle instead of a window. This was the only outside door in the structure. Each of the four walls had a window in the center except the south wall which had a door instead.

there was a 4-foot by 4-foot shelter put over the door to keep the snow from coming in the house door when we were going in and/or out—mostly coming in.

We lived in the sod house about eight years and I don't remember the roof ever leaking. The house was also quite warm. The last two or three years the east end of the north wall started to lean out and had to be braced.

[Inside,] there were 2 partitions across the [short] way, 9 feet [in from] each end making it 3 rooms—18 feet by 18 feet in the center and 9 feet by 18 feet on each end. The end rooms were bedrooms and the center room was a combination living room, kitchen, and recreation room. In the center of the middle room was a post to give additional roof support.

So finally John had land, the fulfillment of a desire he had harbored since marrying Minnie in South Dakota. Under Canada's Dominion Land Grant system, he would receive 160 acres (a quarter section) after showing evidence of working the land and establishing buildings. He could also claim an adjacent quarter section, which he did—the one immediately south of his initial grant.

When the Goose Lake Line was constructed across Alberta,

was established on the railroad two and a half miles east of the homestead. Though Excel was tiny, it lent its name to the surrounding region and eventually, to a nearby school.

John, Minnie and the children lived on the homestead near Excel for the next 11½ years. During that time, four more children were added to the family (after Earl): Harold Bell, August 1913, John Perkins, March 1915, (Mary) Mina, November 1916, and (Gerrit) Lee, June 1918.

Sod houses were usually regarded as temporary structures, but the Wrights lived in the sod house for seven years (or “about eight,” as Lloyd put it above). Finally in 1918 a wood frame house was built nearby and the sod house was abandoned. Even in the sod house, snow would sometimes drift in through cracks around the windows and create little piles inside. Though the wood frame house was undoubtedly cleaner and brigher, it was far less comfortable in the cold Alberta winters. Sometimes even vegetables stored in the cellar would freeze. And water that was spilled on the floor would quickly become a patch of ice. Lloyd told of one of his brothers who was getting ready to go outside. He leaned against a wall while putting his boots on, only to have his feet slip out from under him because they were inadvertently planted on just such a patch of ice.

The family's livelihood was derived from wheat farming, which toward the end was supplemented by raising cattle. In the early years, farming went well (though the family's living conditions never rose much above what would be considered extreme poverty today). But in later years wheat harvests fell off, perhaps due to a combination of less favorable weather and loss of soil fertility. Finally, after the harvest in 1922, John apparently concluded (perhaps with some pressure from Minnie) that it was no longer possible to make a living on the homestead. So that December, Minnie and the children moved back to the United States, ending the “Canada chapter” of their lives. John stayed behind for a couple of years, perhaps hoping that he could still make a go of the farm, perhaps hoping economic conditions would improve and make it more salable. But more on that later…

Lloyd arrived in Canada a child, not quite six. He left as a young man, having just turned seventeen. The only formal education he would ever receive came in the one-room Excel schoolhouse, but it served him remarkably well. Because he had started school late, he was halfway through his tenth grade year when the family moved.

The following chapters are a collection of anecdotes that provide glimpses into life on the homestead. They are presented largely in the order Lloyd wrote them (that is to say, not in any particular order). Perhaps the above summary of the family's years in Canada will provide a backdrop against which these stories can be better understood.

|