Wheat Farming

Over the prairie [were] scattered quite a few rocks and to make it cultivatable it was necessary to remove the rocks from the land. Much time was spent doing just that. Dad had a dream of building a stone house on the place some day and all the rocks were hauled to the site he had chosen on a hill on the northeast corner of the homestead back from the road let's say one eighth of a mile and quite near to the eastern border by where the sod house was built.

The rocks were quite uniformly scattered over the land and varied from egg size to so large that one would make a heavy load for a team of horses to move. There were not many that large but many so large that it was very hard to roll them onto what we called a “stone-boat” which was eight to ten inches above ground—roughly runners about six to seven inches thick and two to three inch planking spiked to the runners. The dimensions were about seven feet long by four and a half feet wide. A stone boat did not last long because being dragged over the prairie loaded with rock wore the runners off quite rapidly. Several were worn out getting rock hauled to make a pile about 70 to 80 feet long, 25 to 30 feet wide and averaging about 4 feet deep. When we went back to visit the site about 36 years later the pile was still there pretty much as we left it in 1922. I think the size of the pile is quite correctly stated but the individual rocks did not seem as large as when we left.

but Mom and Dad stacked the wheat near the buildings. Dad did not go with the threshing crew that year but hauled the wheat from the field and Mom stacked it in several large stacks so that even in unfavorable weather it would not spoil. The stacks were over twenty feet tall. One evening we came home from school and the folks were unloading and stacking the last load for the day. A long ladder was leaning against the stack and Mom had built the stack to a point five or six feet above the top of the ladder. They called it topping off the stack. I decided I wanted to climb up to the top of the stack. I got to the top of the ladder and there was several feet of stack going on up. I thought if I went on up that with the stack curving in to a point that I could make it. Using the stack to help, I went on up till I was standing on the top rung and still couldn't make it. I tried to go up on the stack and was leaning against it and pushed the ladder over backwards. The straw wouldn't any where near hold me so I started my estimated twenty foot drop, and in a sitting position. The Lord was looking after me and I sat down, not on the hard ground, but on the bottom rung of the descending ladder. I knocked the bottom rung off which slowed my descent greatly and saved me from having a much more serious and debilitating accident. In about a week I was getting around in a nearly normal way. And I was learning in a very hard way.

In the eleven years we were in Alberta as near as I can remember, we had only one rainstorm that was like the ones reported in the southeast and south United States. We estimated that it rained about 8 inches in one day. Most of that fell in about four hours but it kept on raining at a lower rate and then off and on.

We could hardly believe water was flowing that fast. That storm was about the only rain that fell on our wheat crop that year. That was our third best crop produced in the eleven years we were there. 1916 would have been the best crop had it not hailed out. 1915 was second best with about an average of about 40 bushels per acre. 1917 was third with probably an average of slightly less than 30 bushels per acre. If we [had] had wheat varieties as they were developed in about the 1960's and later we would have had yields of 2 to 2½ times greater.

There was usually quite an influx of men to help harvest wheat at harvest time—mostly threshing starting in about 1915 in our area and on into the 1920's. With that influx there was usually some interesting and amusing incidents happening. I do not remember many of them but will record a few—not in the order of their incidence, but as they come to mind.

One of the most amusing was that two men did not have transportation so decided to pool their bedrolls and sleep in the edge of a straw stack. As quite often happens at the end of the threshing season, colder weather moved in. These men bedded down in the straw and went to sleep. As the weather grew colder in the night a hog on the farm got cold and started moving around to find a warmer place to sleep and came upon these two men bedded down warmly in the straw stack. They were sound asleep after a hard day's work and did not notice as the hog rooted her way between them. That made the covers too short to adequately cover all three, so [first one would nudge and say,] “Quit pulling the covers,” and [pull them] over the hog to get covered, then the other would get chilly, nudge the hog, she would grunt, and get the covers pulled back over her the other way. When morning came the men found that they had been pulling the blankets back and forth over the hog all night. They did a good job of keeping the hog warm but a poor job of keeping themselves warm.

There were other stories Lloyd used to tell about incidents related to threshing crews, but somehow he did not ever get them written down. Toward the end of the Wrights' time on the homestead, the threshing process got larger and required more help. But earlier on, a threshing crew was about fifteen men. Each seems to have had a specific job. Some ran the binder in the field, which produced bundles of wheat stalks. Some loaded the bundles of wheat onto wagons and hauled them to the threshing machine (which did not move). Others fed the bundles into the threshing machine. Still others hauled the threshed wheat to storage. And finally there were those who tended the machinery. Apparently John worked on the threshing crew at least some years, since Lloyd makes a point of mentioning that he did not do so the year they had to bring in and stack the wheat bundles themselves.

While the crew was working on the Wrights' harvest, it fell to Minnie to feed them. One time, she had baked a pie to be part of their meal. She carefully cut the pie so that each man could have a piece. As the pie was passed around, though, one of the men (an Englishman, Lloyd recalled) took two pieces, leaving another to go without.

The threshing crew ate in the main living area of the sod house. While they were eating, the children were consigned to their bedroom. The wall between the bedroom and the living area was merely boards nailed to a frame. As might be expected, there were small gaps between the boards. The children, with nothing to do but wait, undoubtedly took to peeking through these gaps at the men sitting around the table just on the other side of the wall.

Sometimes when a man would lean back or push his chair away from the table, his back would be right up against the wall. This led to irresistable temptation. The children would poke a needle through the gap and into the back of the unsuspecting gentleman. He would start, feel his back where it had been poked, and finding nothing, eventually resume his position against the wall. Before long, another needle poke, another start, further feeling for the source.

Lloyd was never clear about how long this went on, or whether they were ever found out.

There were various methods of taking care of the needs of the threshing crew. As the threshing machines grew larger and increased in capacity to thresh wheat, they would also increase the area that they would serve. This would mean that they would have larger crews and tend to have mobile units to provide meals and also mobile units to provide sleeping quarters. So when they would move from ranch to ranch there would be quite a train of equipment to go along beside about eight bundle wagons, a steam or an oil powered large tractor pulling a stationary threshing machine, a supply wagon with barrels of fuel oil, lubricating oil, belts, water and other equipment, the cook wagon, the bunk wagon, etc, etc.

About the time we moved to Oregon there was beginning to be a trend toward combines and away from stationary threshing machines. Harvesting and threshing would be done by combining both jobs, doing them both with one machine known as the combine. Harvesting grain was done mostly by hand for thousands of years and in the twentieth century (and back a little into the nineteenth) the operation would be combined so that what used to take months is done in one day.

Jim McLeod had more trouble with runaway horses than anyone else in the area as far as I can remember. I recall three very expensive ones, one each with a two-bottom plow, a grain drill and a grain binder. The one with the plow was the most spectacular. All happened with a four-horse team that was stopped for various reasons. Plowing was the hardest work and a team was allowed to rest a while in the morning and afternoon. One afternoon the team rested a little longer than necessary and got restless. Next thing they were galloping across the prairie with the plow bouncing around uncontrollably, sometimes right side up and sometimes up side down, all the while with the horses galloping in all directions. When the plow would land right side up the sod would fly in the air many feet and in pieces up to 15 to 20 feet long till the plow would bounce on its side or upside down again. Finally the plow hit a large rock that sprung the beams and the plow bottoms settled down into the ground so deep that it stopped the team.

Some time later Jim got a new grain drill and was

and stopped to refill the drill box when again the team took off at full speed. A new telephone line had been put in about a year before right by the field he was planting and it so happened that the new drill had two tongues and was drawn by a four-horse team (two horses on each tongue). For some reason, two horses decided to go on the left side of the pole and the other two decided to go on the right side of that same pole. That wrapped the drill nearly all the way around the pole. Well, no more drilling that day or for several days after. The drill stayed wrapped around the pole for several days. Then one day it was gone.

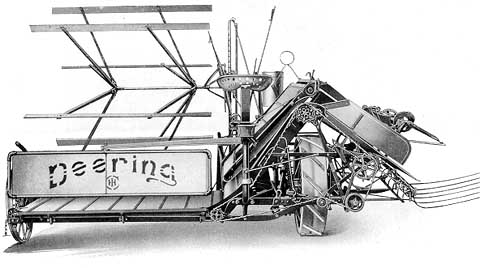

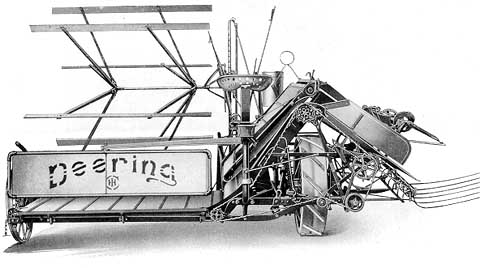

| Deering grain binder, perhaps not identical to the one Lloyd describes, but similar. The entire machine was powered by the large cleated wheel on the right, that turned as the horse team pulled the binder forward. |

The time of year seemed to have nothing to do with the horses running away. The two runaways mentioned above happened in early spring and later spring. The next one happened in the fall and involved a grain binder. A grain binder was a machine that was quite complicated and needed to be stopped once in a while to keep it in good working order. To give a little idea of how it operated, this might help: It was driven by one large wide drive wheel about four feet in diameter with cleats on it to keep it from slipping instead of turning to drive the whole operation. I will follow the grain through the machine rather than the drive train. An eight foot sickle cut the grain which was laid back on a moving cleated canvas also about eight feet long by a reel also eight feet long. The eight-foot canvas carried the cut grain to the right where it was elevated by two canvasses running about four inches apart, one above the other feeding the cut grain onto packers till there was enough to make a bundle about ten inches in diameter. This activated a large needle and knotter, which wrapped twine around enough grain to make a bundle of the desired size and knotted the twine. It was called a binder because it bound the grain into bundles. The cleated canvas was a little over sixteen feet long and on rollers about four and a half inches in diameter giving it an operating length of about 8 feet.

Again, the team was stopped while the binder was being adjusted, unplugged, oiled or whatever was needed to make it operate properly, when the horses seemed to think they had stopped long enough so took off and as usual at a higher rate of speed than normal operation and as usual with disastrous results. This time they ran into a deep road ditch, which collapsed the large drive wheel as well as collapsed the more delicate parts of the machine. Another piece of needed equipment mostly destroyed…

|