First Memories

Now John Wright was a city boy, having grown up around Chicago. What drove him to choose farming as a vocation is impossible to discern. Nevertheless, he farmed rented land around White Lake for several years. But he very much wanted land of his own. The Rosebud Indian Reservation in south central South Dakota first had been opened to white settlers in 1904. Some of that land was still available, and was being distributed by lottery. John put in for a homestead. Minnie's single sister Anna did as well. Anna's name was drawn. So John moved his family west with Anna to help her get established, and to wait for his own name to be drawn for a homestead. But John's name was never drawn.

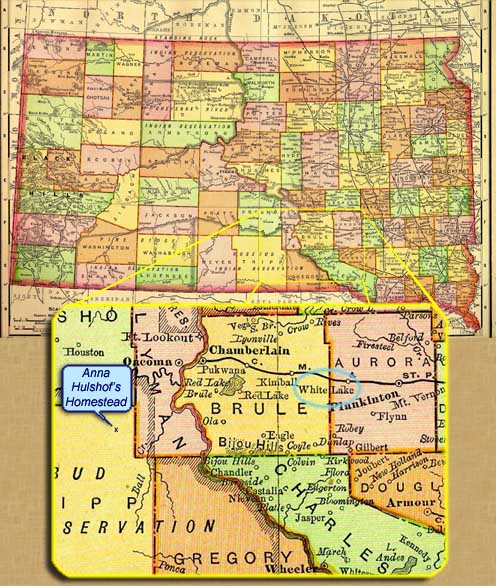

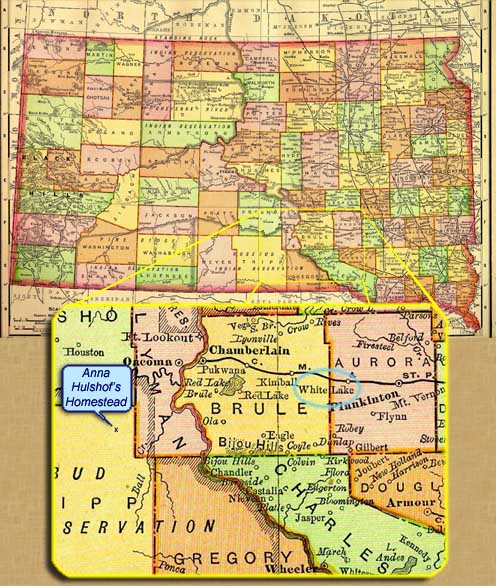

| 1895 map of South Dakota, with inset indicating the location of White Lake (circled in blue) and the location of Anna Hulshof's homestead near present-day Hamill, South Dakota. |

Lloyd writes of South Dakota memories that must have occurred around Anna's homestead. He was approaching his fourth birthday:

Three things that happened in South Dakota fixed themselves firmly in my memory. All had to have happened in the summer and/or fall of 1909.

1. Our Aunt Anna, Mother's sister, was milking a cow in our yard in the evening and my sister Anna and I were wandering around. Anna [my sister] was picking a few late wild flowers. Soon she ran to her aunt and said, “There's a froggie over there.” “There can't be,” was the answer. But she was very insistent. Upon investigation the “froggie” turned out to be a rattlesnake. My mother, upon being notified, came from the house and quickly took care of the danger by killing the snake. Mother killed several rattlesnakes in South Dakota with whatever weapon she could get hold of quickly, according to stories told in the family. I witnessed an instance when Dad killed one with a Colt pistol he had. It was still squirming after several shots.

| The Democrat wagon (sometimes “Democrat buggy”) had two bench seats, but the rear seat could be removed to create a cargo area. This versatility made it a popular type of wagon. It was also called a “station wagon”, and that term was later applied to a type of automobile with a similar feature: rear seats that folded down to create a cargo area. |

2. Dad took us out for a drive with a team and light wagon called a Democrat. On this outing a snake called a blue racer was frightened and headed for a creek we were driving by and swam swiftly across. The reason this is planted so clearly in my mind, I think, is that although they were there I had not seen one before and the swiftness with which it moved impressed me. Another thing is that it seemed inappropriate in my child's eyes for a land animal to be swimming. The rattlers I had seen were never in water or moving so rapidly, and the other land animals I was acquainted with were not usually in the water, though they often waded in it.

3. In the fall of 1909, Dad, my older brother, and I were cleaning up around the yard and garden (I was of little help), when we found a small, late watermelon. We all sat down by a small haystack in the sun and sheltered from the chilling breeze. Dad cut the melon into pieces with his jack knife and we ate it. As I remember it, the melon did not have a very good flavor but the coziness of the physical situation and the warmth of the afternoon and the sharing made the experience a wonderful memory—especially

By the

John was getting restless. He despaired of getting

Lloyd writes:

Dad wanted to get some land to farm, but the homesteads were all taken. He had a four-horse team and a little farm machinery, but no land to farm. He then learned of a need for horses in the Seattle area. He had a brother, Richard, living in Seattle, so decided to move there.

John loaded the family's belongings, farm equipment, and horses into an immigrant car and the family moved to Washington by train. They lived briefly in

before settling in Snohomish.

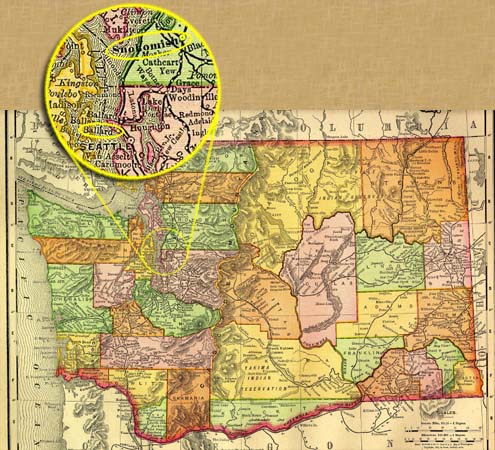

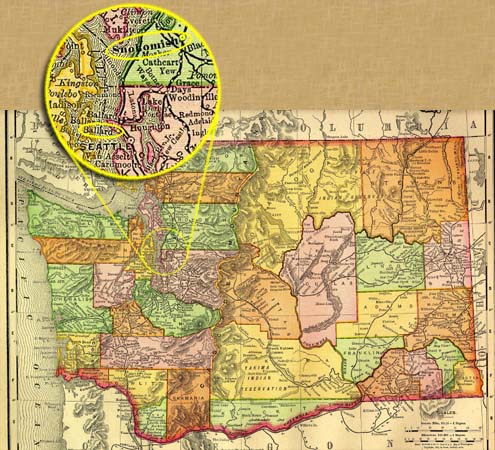

| 1895 Map of Washington State, with inset showing locations of Ballard and Snohomish in relation to Seattle |

Lloyd writes of several experiences while living in Snohomish. He was four and a half or five at the time.

An event early the next spring, probably about February or early March of

left an imprint that is still very distinct in my mind to this day (about 80 years later).

We got up one morning and the ground had a thick coating of hoarfrost on it, which was glistening in the early morning sunlight. It was quiet—an unusually beautiful morning. To add to the joy of the morning, we were just ready to start our breakfast in front of the large window facing east with the sun shining in. Mother had a large bowl of steaming oatmeal on the table resting on a soup dish to protect the table from the heat of the bowl of oatmeal. The steam was rising from the hot oatmeal in the sunlight. It was a beautiful setting. We were all in our places. Dad had just sat in his place with his back to the window.

At this moment of anticipation a terrific explosion shook the house, shattered the window, and blew glass all over Dad, the table, the breakfast, and a good part of the floor. The large bowl of oatmeal rose high enough that when it came down it broke the soup bowl in two. My older brother saw something quite large flying through the air outside.

The beautiful setting had instantly turned into an ugly disaster. It is the first disastrous event I remember experiencing. The lovely atmosphere and setting for our breakfast, as well as our breakfast and the window, had been completely destroyed. We had no idea what had happened to cause it.

The rest is hearsay. About a half mile away and downhill from our house a project was underway that required blasting out large stumps. (We had heard the blasting in days previous, but nothing nearly this powerful.)

It seems that one man would go to the project early, build a fire to warm the dynamite to improve its performance. Apparently the fellow warming the dynamite that morning had been drinking, but he was alone, so what he did no one knows for sure—got it too hot? hit something?… His body was found about

in the Snohomish River. One shoe was left behind. What my brother had seen flying through the air was his body. He must have been standing over the dynamite when it went off, the way the body went up in the air.

I was getting old enough to appreciate the freedom and room to roam in unused areas. A large area near our home had been cleared of timber and had a few years' growth of brush (about seven to nine feet tall) on it that we wandered through with a sense of adventure during the summer of 1910. My older brother and I spent quite a little time roaming and exploring this area. We extended our roamings deeper and deeper into that “wilderness”. As we got acquainted with the area, we expanded it [our “territory”] a little nearly every day.

| Interurban “train” in the vicinity of Martha Lake, southwest of Snohomish. This clearly shows what the Seattle-Everett Interurban track and trolleys looked like. The Interurban line to Everett had been completed just a few months earlier, in April 1910. |

One day extending our range a little we found two new things: a white shirt in the brush, and the tracks of the interurban rail line that ran from Seattle to Everett. We dragged the shirt around a while, and finally decided to lay it across one of the two rails to see what would happen to it when it got run over by the steel wheels. We came back the next day and found that they had stopped the interurban train and laid the shirt off to the side of the track instead of running over it. We laid it across the rail a second time. When they came back the next day the shirt was laying across the track again. This time the crew carried it 'way back in the brush and hid it. When we came back it was nowhere to be seen. We scouted around quite a while, searching in widening circles, and finally found it hidden in the brush quite far from the tracks. At that point, our project changed from discovering what the cars would do to the shirt to tantalizing the crew.  | Interurban trolley in Everett |

We laid it across the rail a third time. We were never able to find it after that. We imagined what the train crew was saying by then, but couldn't understand why they wouldn't run over it. End of project. We turned to other explorations, since this one had turned out differently than we expected.

In our yard was a young Douglas fir tree about 7 or 8 inches in diameter with the bottom limbs trimmed off just high enough that, stretching as far as I could, I could barely touch the bottom limbs. My older brother could easily get hold of them and climb the tree as I stood below and yearned to do the same. From time to time I would try though and [one time, I] finally got the tips of my fingers over the limb. That was enough for me to make it on up. Young Douglas Fir trees usually have thousands of pitch pockets in the bark. I must have broken half or more of them. Anyway, when I came down from that tree I was pitch from head to foot. Very few times did I see my mother more disgusted with me. My brother was big and strong enough that he didn't have to shinny up so he broke few of the pitch pockets. I am not sure what the most compelling reason was but I never climbed that tree again. Perhaps once I had conquered it there was no compelling reason to do it again. Getting all covered with pitch and getting it cleaned off was quite a deterrent. Maybe my mom's disgust with me was the biggest reason.

The work John expected to find in the Seattle area didn't materialize. Lloyd writes:

By the time the family arrived in Seattle, though, the need for horses had evaporated. Horses were being replaced by donkey engines and other mechanical sources of power.

|